Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

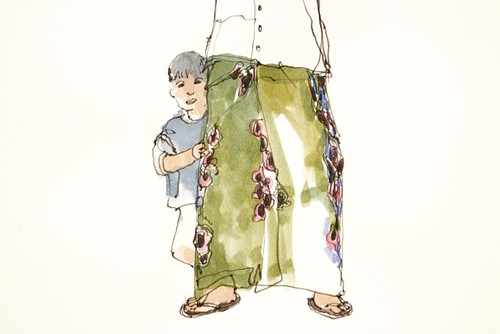

100 years ago, rice farmers near Songhkla, Thailand would send their freshly-cut rice to the Red Rice Mill to be processed for sale. Rangsi Ratanaprakarn’s father ran the mill and raised his family across the street. The following is an excerpt from his short autobiographical book, Growing Up at the Red Rice Mill, featuring stories from his childhood. The artwork is by the amazing Malaysian artist, Kiah Kiean Chng at KaKi Creation in Penang.

You can DOWNLOAD Mr. Rangsi’s e-book for free.

“My father loved this place so much. I want to keep it to now hand it over to my children. Because of the Red Rice Mill, my father and our family had a good life. I could go canoeing on the lake. Learn to drive a car. I went go to college. All the stories I told you. Later I started my own company and have travelled all around the world. This was all made possible because my father and mother worked hard – and because of the Red Rice Mill. I learned from my father the importance of a good education, working hard, and of helping other people.”

“I remember walking into the rice mill. They burned rice husks to heat the water boiler. The smoke went up the stack but because of the turbulence in the air, you could smell the smoke throughout the rice mill. It didn’t smell bad – not like burning plastic today – but it wasn’t very pleasant either.

The Red Rice Mill is four stories tall. You can see lots of very small, square windows on the outside. They were built for ventilation. Back when the mill was in operation, there were people who worked on each floor. Their job was to make sure the belts and pulleys connected to the steam engine worked correctly. But it got hot inside, so they could open these windows and the air would come in and cool them down. There wasn’t any electricity so the windows also provided light.

In the morning, my father would leave the house and walk across the street to the mill. He’d go through two small doors, now to the right of the Songkhla Heritage Society’s glass office.

Right from the beginning there was a mistake in the design of the rice mill. The smoke stack you see today looks so nice, but it was never used. When my father’s uncle designed the rice mill, he ordered a steam engine from England. Before it arrived, he decided to go ahead and build the smoke stack they would need to attach to the boiler. That way, when the engine and boiler arrived, they could get started right away. They imported high quality bricks from India for this first smoke stack. It was a good idea, but for some reason, the Chinese carpenter didn’t read the plans correctly. The first smoke stack was built in the wrong place. They put the boiler and engine on the other side of the rice mill. That meant that they then had to build another stack so they could get a draft to the boiler. This second stack was the one they used for so many years, but it was made from cheaper, local bricks. It wasn’t as strong as the first stack made from bricks imported from India. So after the steam engine was no longer needed, they decided to dismantle the second stack. They thought the cheap bricks would be too dangerous to leave up, so it was dismantled. The smoke stack you see today was the one made from Indian bricks, the first stack, which was never used.

The breeze would come about 6 or 8 months a year. so it helped to blow and send the draft through the boiler and through to the stack. The boiler and engine were set up on the other side of the rice mill. In the corner, there was a boiler. With a fire, they boiled water which powered the steam engine. The steam engine turned one big wheel. From this one wheel there were many pulleys running throughout the rice mill. This was how they ground the rice. Today you can still see many places where the pulleys and belts ran. The roof in the main hall was much lower than now. Then in 2491, this area (the old roof) was demolished and rebuilt in concrete.

It was very noisy in the rice mill at all times of the day. You could hear a boom, boom, boom. That came from the steam engine. There was only one cylinder in the steam engine and it would shake the ground like a drum. It had a very low tone. The noise didn’t bother me much but you could feel the ground shake. I could feel it at the house too. It went on all day, all night – but not all year. They only ran the engine about 8 or 9 months a year. Then they had to stop it and clean the boiler. They did this every year. Years later, when they stopped using the engine, people in the neighborhood complained that they missed the low sound and beat of the engine. They said they couldn’t go to sleep without that drum-like rhythmic beat.

In addition to the boom, boom, boom – you would hear the clack, clack, clack of the belts and parts turning all around the mill.

The workers didn’t talk much. They knew what they were doing. There was no yelling, but they did have to speak loudly to be heard over the noise of the engine and mill. They would change shifts every 8 hours. My father had a bell that was rung to signal the shift change. I still keep this bell, which was made in England.

Originally, the pulleys and belts went up four stories high because they used gravity to mill and sort the rice. They carried the rice up four stories and then let it go. At one spot on the 2st floor, the rice would enter a cyclone to separate the light materials and the rice grains.

The separator was on the 2nd floor. This saved energy. If they had kept the separator on the ground floor they would have had to bring the rice up first. So they put the separator up way up and saved many steps. Finally, there was a shoot and three different bags which were lined up together. The different bags held, perfect rice , broken rice, and then some other things like the rice husks. The cyclone is still there. It used gravity to separate the rice. When it turned, the light things just got out on the top. and then they come down. The heavy particles, like rice, went through. Everything came to the bottom. This was the last step. When the rice was processed there would be big bags on the warehouse. Each rice bag was about 100 kilograms. The workers had to carry them outside on their shoulders.

The main entrance, which most people use today, was modified after World War II. My father raised the entrance so trucks could easier come in and out. They used the rice mill to store rubber after World War II.

The current dock was built after World War II. Before that it was a wooden pier. It was much shorter back then. IN those days, the water was quite deep. Even after World War II it was deep. I measured then at 6 feet. Now it’s only 4.5 feet deep. It is silting up after the government built the sea port, which blocked the current. As a result, the water moves too slow and has interrupted the natural flow of the water.

The little red building on the dock was also build after the war. When they knocked down the original roof, they used the old material. This little building was the cold storage, to keep ice for the fishermen. Originally, there were only 2 or 3 ice factories in Songkhla and they made big blocks of ice. So we had to order ice in advance and keep it in this building. How did they keep it cold? There was a side wall and my father put some sand, which acted like an insulator to keep the temperature down. Then they crushed the ice. This was about 2530 – about 30 years ago. After they stopped exporting rubber, we used the rice mill to supply the fishing boats. Twenty years ago there were 500 fishing boats on the lake. Now there are only about 100 left.

The upstairs behind the glass Songkhla Heritage Society’s office was remodeled three years ago to make toilets. Before that, there was a water tank there. It was quite thick. We had to pump water up there for the water boiler. The water from the lake was too salty to use in the boiler so we had to use fresh water from our well at the house. There are two shallow wells at my house and there is a pipeline under the road. Back in those days, the street was just dirt, so it was easy to built the pipeline. The water tank here was just extra because the two wells from the house weren’t enough. We piped fresh water up and then all the way across (the street) to the other side where the rice mill is. It was very complicated. They didn’t use the water tank at the mill much. Use to there wasn’t any traffic here. We used steam engine to run a small pump.

When I was young, the other side of the lake looked much further away. Perhaps that is just my personal feeling. But now there is lots of development there. Back then I didn’t see any buildings at all. It was just green. People who committed crimes, escaped from Songkhla and had to go to that side to hide.

The water in the lake was much cleaner then. You could see a lot of fish swimming by. Every time you came to the dock, you would see sea hawks who would dive all over the place catching fish. Now there are no birds, just pigeons.

The boats who brought the rice were Chinese junks which sailed around the lake. They would come in for one week and had to wait for the right wind to sail back home. Some came from the ocean, but only for a short time. Normally they came only by the lake – not from the open sea. Out there, there was no shelter.

I don’t think too much about my age. I think I will be here a couple more years. As long as I can help myself, that’s ok. I enjoy life and have a lot of friends. I don’t think too much, travel a lot, have lots of friends, and take it easy. My life is both in Bangkok and in Songkhla.

If I don’t take care of the rice mill and fix it up, it will quickly be gone after I die. This is an old building. I run it now at a loss. If the building was gone tomorrow i would feel so sad but I wouldn’t rebuilt it.

My time is over. Now I want to support my son and family and the Songkhla community to make their dreams come true. This is my legacy. I think about my father and mother when I am here. My father didn’t have a chance to go to college. He wanted to – but his uncle, who ran the rice mill back then – said better come and work for me. So my father obeyed and became a clerk for his uncle. He earned a salary of 20 Bhat a month. When he married and had children, his uncle raised his salary to 50 Bhat.

But that didn’t stop him from learning and educating himself. He taught himself to speak and write English. He could speak Sanskrit and some of the local dialect Malayu. He read newspapers and magazines to learn about how steam engines work, how to improve the rice mill, and become a better business man. I think that is why he donated money to the local universities when he got older. He thought education was important in order to be more prosperous and happy in life.

Now, I want to give back to Songkhla, my home town. When I retired and moved back to Songkhla, many families here in the street had moved out. Now – also together with the Songkhla Heritage Society – we are trying to improve the neighborhood. We help preserve Songkhla’s history and repair the old buildings. Songkhla’s old town and the Red Rice Mill should be a joy and happy place for Songkhla’s people and our visitors. Perhaps others will be inspired by my family’s story and the Red Rice Mill. I want everyone in Songkhla to have the chance to live a happy and prosperous life like I did.

There are lots of rich people in Songkhla but just being rich is no good. Nobody lives alone. We are all here together. You have to be part of the community. With the support of my friends here in Songkhla, we work together to make the old town and the Red Rice Mill a good place to visit. I can’t do everything but I can help to kick things off. Hopefully other people in Songkhla, who think the same way, will work together. We will work together to make the old town a place that inspires others to live prosperous, happy, and generous lives.

For many of us, dreams are about “getting” something; they’re selfish….For Dhurba, dreaming means giving.

“My parents are farmers. I never finished school.” He came from a poor village in the jungles of Nepal and worked as a waiter to tourists who came on safari. One day at the restaurant – he had a long chat – with a couple – visiting from the Netherlands. They asked him – an unusual question: “They asked me my dream and I was surprised a little bit.”

But with NO cash, to make his dream come true, Dhruba forgot about his dream and the Dutch tourists. “Then after 5 -6 months they send me the letter. The say we have money for you and please send us your back account. and I was surprised. I couldn’t believe it. I thought they were making a joke.”

With a backpack full of cash – Dhurba bought land from a rice farmer and starting building a hotel. A hotel he named “Sapana Village”. “Sapana means dream and I work for the dream.” Sapana Village looked nothing like other hotels in the jungle. He built his lodges to look like a traditional Tharu village. “Tharu are the original people and they should get something back from the tourism but nothing they get.”

But with NO cash, to make his dream come true, Dhruba forgot about his dream and the Dutch tourists. “Then after 5 -6 months they send me the letter. The say we have money for you and please send us your back account. and I was surprised. I couldn’t believe it. I thought they were making a joke.”

With a backpack full of cash – Dhurba bought land from a rice farmer and starting building a hotel. A hotel he named “Sapana Village”. “Sapana means dream and I work for the dream.” Sapana Village looked nothing like other hotels in the jungle. He built his lodges to look like a traditional Tharu village. “Tharu are the original people and they should get something back from the tourism but nothing they get.”

So in addition to the typical tourist activities – elephants rides and safari trips – Dhurba asked Tharu families to show his guests their traditional ways of life. “And 50% of the profit go to the local community”. Dhurba now puts his profits in local development projects.

For many of us, dreams are about “getting” something; they’re selfish….For Dhurba, dreaming means giving.

Find out more about Dhurba and the development projects his Sapana Village are spearheading at sapanalodge.com.

Music by Binod Katuwal: youtube.com/channel/UCSLPg–3m41JPZh7EgiYuiA