Travels with OXLAEY

- Week 1: The Death of George Town

- Week 2: TIN MAN

- Week 3: CUT & SHAVE

- Week 4: Tourism is a Happy Meal

- Week 5: Bloody African Feet

- Week 6: Willem’s Windmill

The Death of George Town

A murder. It happened in historic George Town, Malaysia. The heat radiated up from tar-pitched asphalt streets. Once upon a time you could feel a cool ocean breeze in George Town and smell the sea and morning dew on the grass. Back then, old mansions built from teak with colorful tiles lined Penang’s North Beach. No more. Now, you only smell dirty car exhaust.

On the day of the murder, a man woke up – although it could have been a woman. It could have been anyone, a person like you with ten fingers. Hungry around noon. Feels lonely sometimes. An honest worker, like mother and father had taught.

A man woke up in a concrete apartment building situated right next to the sea, but he couldn’t see the historical Straits of Malacca. This shipping lane where wood, tin, and rubber were shipped from southeast Asia all around the world. Hundreds of years ago, migrants came to George Town from India, from China, and from today’s Malaysia. They all hoped for a better life. Together they built a new city, George Town.

The man stepped out of his apartment, but all he saw was another box of concrete, hundreds of dull uniform windows with bras and underwear strung out outside to dry. He walked down the trash-strewn stairs, because the elevator was out-of-order, again. In the parking lot, he mounted his rusty motorcycle and drove along the North Beach in George Town as the sun came up. It was a public holiday, but he had a job to do. A security guard saw him approach and then opened two opaque metal gates, the kind that are put up around building sites. To hide crimes committed.

The man drove inside, parked and climbed up into to a yellow, powerful machine. A backhoe. It’s a machine like a World War II tank with a small glass cabin perched on top. Inside this cabin are levers and buttons to swing a huge metal claw on the outside. The man climbed inside, inserted a key in the ignition, and stretched out his hand to start the machine. His finger reaching for the start button. He’d been hired to tear down an old bungalow built long before he was born.

He looked across at the wooden building and in flash – a memory triggered just like a particular smell or notes from a song will do. The man sitting in the backhoe was transported away. He saw two hands holding him. His right hand gripped by his father. His left hand embraced by his mother’s. They were walking together – perhaps past this very same bungalow. Or they might have been walking through Little India or past the mosque in Aceh Street.

He couldn’t quite make out the details, but they weren’t that important anyhow. More powerful was that he could remembered the smell of his mother’s clean clothes, the slant of his father’s mustache, the sound of his siblings’ laughter. He recalled the tingle of being so intensely loved and sheltered by his parents who had died so many years ago.

For this fraction of a second he felt so intensely alive – staring out at that old building – that he forgot his poverty. He forgot that the rent was due. Forgot his shoes were wearing out. Then, like a bird disappearing into the sky, the moment passed. The man had never heard of “historical preservation” or “heritage”. He just wondered, looking at that old bungalow, why it had to be torn down. This old building that had given him such a beautiful moment of joy.

Then he snapped out of it, his finger searching for the plastic start button as he remembered overdue bills. The machine roared to life and he ripped the old building down.

On February 9, 2016, a Category Two Heritage Building, the Runnymede, was reduced to rubble. Another link was lost to George Town’s (UNESCO-protected?) history.

No blood was shed. The police never investigated. But I’ve been told that this marked the death of George Town nonetheless.

More next week….

TIN MAN

I met the Tin Man, the first time I visited George Town, Malaysia.

After a plate of char kway teow for breakfast, I lost myself somewhere between the onion-domed Kapitan Keling Mosque, Chinese shrines with smoldering joss sticks, and Queen Street’s neon-colored Indian temple. Way back in 1786, the British established George Town on the island of Penang. The city made it easier for them to strip southeast Asia of it’s raw materials – wood, tin, and rubber. As George Town grew, sweaty bodies from all across the British Empire filled the city. After World War II, the British withdrew and George Town became part of an independent Malaysia. George Town’s mix of colonial and Asian cultures slumbered, hidden in plain view, until 2008 when it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Since then, more and more visitors come each year. Outsiders like me.

I found myself walking along Beach Street past run-down shophouses selling tangy-smelling herbs, a small printing press, a paper recycler. I heard the clang, clang, clang of metal striking metal and saw the Tin Man. He squatted, Asian style, in the shade of his ground-floor workshop in a white-walled shophouse. He wore a white t-shirt, had short, mostly grey hair, and was making a mailbox.

“My name is Mr. Chee Hwa Khaw. I work with tin. I’ve been doing this for decades, since my childhood.”

The Tin Man’s shop is full of old metal-working machines. None of them are used much anymore. Factories in China spit out tin mailboxes and similar items by the thousands per hour.

“You can’t make money nowadays, making these kind of things,” says the Tin Man, gesturing at the mailbox. The corners of his face point downwards, frowning. His left hand turns palm up, fingers slightly spread, hoping to catch an answer.

Before UNESCO, there weren’t really any tourists in George Town. No frilly cafes with air-conditioning. No cutsie street art. No selfie sticks. George Town was for the working class.

“In my 30’s I got sick. I had a family with small children. I was anxious. Nervous.” The Tin Man’s body scrunches up as he describes those days.

“When I went to go outside, I got so scared, I couldn’t leave. As soon as I walked out the door, I’d break out in a sweat. I thought I would die. The doctor said, ‘You have an anxiety disorder. You have to walk on your own. You have to stand and not run. If you run, you’re lost.’ I had to follow the doctor’s instructions. I had no choice. Sometimes I start to walk, get scared, and run back. Bit by bit it worked.”

The Tin Man drills a few holes in his mailbox with a very durable-looking but worn metal press. “Old things were made very strong,” he says gesturing to the machine. “Even when they’re old, they don’t break down.” There’s a certain amount of pride in his face.

“Things today, aren’t meant to last. They break down easily.” He grabs a hand file and scuffles back to the front of the shop. He squats again, smoothing down the rough hole puncturing his metal mailbox. “These kind of hand-made things take time.” He attaches a few bolts and rubber washers to the mailbox. “That’s enough. Finished.”

One month later, Mr. Khaw closed his shop and retired.

More next week….

CUT & SHAVE

Like a tropical storm, gentrification has made landfall in George Town, Malaysia – washing away many old businesses and long-time residents. People like the Tin Man, or the recycling lady, Mrs. Lien, and the elegant Mr. Ong, who ran a chemical retail shop in Chulia Street for 63 years. Of course, there is a flip side. Now there is room in George Town for a new generation to put down roots. People like Elyas, who brought the scumbag back to life.

Elyas Bin Yunoos is a barber. He’s slight of build, has a fuzzy wanna-be mustache, and big, dark eyes. Although he parts his hair on the side, Elyas prefers to wear a hat and white jacket when he cuts other people’s hair. Elyas is most probably the best barber in the world, but painfully slow. Maybe that’s because he never went to a barbering school, where the instructor would have taught him to snip and flip his customers as fast as possible to maximize profits.

“Our concept here is vintage haircuts which is why we have these old barber chairs in here,” says Elyas. A few years ago he was watching YouTube, when he stumbled upon a video by two famous barbers. “They’re the Schorem barbers from the Netherlands.” These hipsters barbers from YouTube combined haircuts, with tattoos, and a little bit of marketing-savvy to help rekindle a global interest in classic men’s cuts like the scumbag, undercut, or executive contour. “I watched them on YouTube. I studied their techniques. Then I felt like I had found myself. Yeah – I found the real me.”

Elyas’s shop is located in a narrow shophouse next to the old Aceh mosque. He’s training two apprentice barbers, his friends Faizal and Fazil. Most customers have to wait their turn outside on the porch. Inside, air-conditioning cools razor-scraped heads under neon lit lime-green walls. There’re posters of different mens’ classic cuts, a picture of James Dean, cut out of a Malaysian star from the 1950’s, and several prints of Eylas posing with his krew. When he’s cutting, Elyas’s face is focused. “We only do cut and shave, and we can use our clippers to cut as close as a razor.”

Elyas’s named his barbershop, Son & Dad, in honor of his father who also cut hair. His family and faith are central parts of his life. “Everyday after prayers, I call on Allah for his blessing. Thanks be to Allah. My confidence has grown as I’ve become more popular.”

In many ways, Elyas and his old-school, modern-times barbershop is just an extension of the traditional in George Town. Elyas doesn’t smoke. No tattoos. His wife is in the back with his newborn. He cuts all kinds of hair, be it Chinese, Indian, Malay, or European. But he does have a Facebook page, his shop is air-conditioned, and he learned to cut the scumbag thanks to that global phenomenon known as YouTube.

Like gentrification, a bad haircut is painful to look at, but it will grow out again. Just sit down and put your trust in Elyas – barber, family man, and a true George Town gentleman.

More next week….

Tourism is a McHappy Meal

McDonald’s, Burger King, Kentucky Fried Chicken – all these companies have one thing in common. They engineer “food”. In a single Spicy Chicken McBite you’ll chew on only the tiniest bits of real chicken. The rest of it is sodium phosphates, citric acid, sodium aluminum phosphate, monocalcium phosphate, tapioca maltodextrin, onion powder, etc… Read the full list for yourself. This is not real food. That’s why you’ll eventually grow fat and stupid, if you eat enough fast food.

But did you know that cruise lines, leisure travel companies, even the Lonely Planet can also make you dick and dumb? That’s because the tourism industry works just like fast food companies. Tour companies slice up countries and cultures, mash them up with fake glossy pictures, air-conditioning, organized activities and… abracadabra! You, the consumer, purchase bite-size travel happiness. Uniform. Pleasurable. Risk free.

For example, the world’s second-largest cruise line, Royal Caribbean, has a five night “Spice” tour. The ship docks at George Town, Malaysia at 5 PM. By then, of course, it’s getting dark. George Town’s unique craftsmen and historical sites are all closing for the day. I guess tourists could out to eat some of George Town’s famous street food, but most I see go back to the ship early. They prefer to eat on board, because their food is already paid for. Anyhow, the boat departs at midnight. At least they’ll have time for a selfie.

“Independent” tourists aren’t any better. If you take a closer look at backpackers in Thailand, you’ll notice that most use a guide book (or digital app) like Lonely Planet. But because so many backpackers use the same book – millions of American and Europeans all magically meet on the same beaches. The hostels, homestays and restaurants pop up to meet their (budget) needs. In the morning these independent-striving tourists all eat banana pancakes, which is what Thai hostels have discovered is most universally eaten by all their customers. Everyday Thais don’t even know what a pancake is. They eat breakfast dishes like rice porridge with pork, fish curry with rice, rice and anything… but never banana pancakes.

What’s the the point of traveling if there’s no engagement with local people, local food, local hotels…. local life? In the end, most tourists remain just as ignorant about the world as they were before departure. They never discover that strange-food gut wrenching, sometimes dangerous but always exhilarating thing we call Life.

More next week….

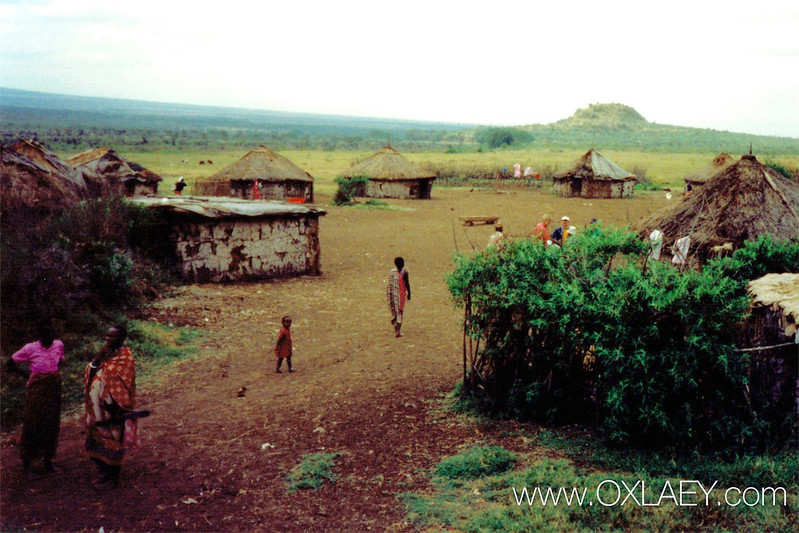

Bloody African Feet

From my entire trip to Africa, the thing I remember most were his bloodied feet.

When I was 17, my grandmother, Clara, told me she wanted me to go to Kenya. She drove me to a photographer to get passport pictures and then to the doctor’s for a few shots. Then, I stuffed a suitcase, packing in two pairs basketball shoes. A few weeks later, I flew with a handful of other teen boys and a couple of male chaperones to Nairobi, Kenya. It was my first time to travel outside of the United States, where I was born.

In the 1970s and 80’s, my grandmother visited South Korea, India, Spain, and Alaska – just to name a few destinations. She almost always travelled with a group from her Christian church. I suppose it was the method she found to safely explore the world. She heard out about a two-week missionary trip for young men and paid for me to go. I remember being indifferent before we left but that changed when we landed in Nairobi.

A short, 42-year old Baptist missionary with curly hair, Ralph Bethea, picked us up. After a good sleep, we rode to Mombassa, on the Kenyan coast, in the back of a pickup truck. Once there, we went to a handful of rural churches, replacing their mud and sticks walls with wooden planks and concrete. We took quite a number of fun trips. I have pictures from our safari tour, from inside the grand mosque in Mombassa and even of African tribal warriors bearing scars from their encounters with lions. Funny, however, that I never took a photograph of his feet.

During the middle part of our trip, we touristic missionaries hosted a basketball tournament at the Mombassa Baptist High School. While American kids assumed we were the next USA dream team, on the court the African kids chewed us up like the animals I saw on safari, gnawing through bone to suck out the marrow. During one particular breakaway, I looked down and noticed that the kid I was (theoretically) guarding wasn’t wearing shoes. His feet were bleeding. Perhaps someone had landed on one of his toenails or something. None of the African kids paid him any attention. Several, in fact, were playing without shoes.

As soon as the game ended, I jogged over to my little gear bag and pulled out the extra set basketball shoes I’d brought, a pair of Nike Air Jordan’s. Not thinking about it too much about it, I gave the kid my pair of shoes. His name was Phillip. The African kids swarmed to look – as if the shoes were made from gold. Later, our chaperoning missionary would make a big Jesus deal out of it, but nothing religious was on my mind when I gave away those shoes. The kid, Phillip, simply didn’t have any to play in. I had an extra pair. I mean – isn’t that what anyone, anywhere would do? Share with another person in need?

You might think that my first big trip abroad made me want to travel forever. But it didn’t. When I came back, life simply went on. I graduated high school then left for college. I guess from the whole trip to Kenya, the image that stuck in my mind the most, was just the image of Phillip’s naked, bleeding feet.

More next week….

Willelm’s Windmill

I’m astounded again and again by the billions and billions of homo sapiens who choose to live amazingly dull lives. You probably know someone who became a doctor or engineer – NOT out of passion – but because their parents told them to. I feel like Don Quixote battling windmills, trying to convincing people to follow their passions, instead of chasing the cash, when choosing a profession.

You used to see windmills everywhere in the Netherlands. Now most of them have been torn down, to make space for new apartments to house all those doctors and engineers. But in Gouda one majestic windmill still stands and if you see it’s sails turning in the wind, you’ll know that Willem Roose is at home, grinding flour.

I walk inside the base of the windmill. It’s dark. It smells earthy with a hint of old wood. Willem leads as we climb up steep stairs to the first, second and then third floor. Third floor. We walk outside on a skinny platform, where Willem stretches old cloth sails across the windmill’s blades of wood. “Let’s try it full speed,” he says and the windmill begins turning – faster, and faster and faster.

I climb, inside, up to the very top floor of the windmill. There I can see the power of the wind. The outside sails turn a pole and then many huge wooden gears. They finally rotate two huge slabs of stone. Willem pours raw grain into a shoot. The two stones grind against each other, crushing the grain into flour. White flour pours out from the stones, down a wooden slide into a cloth bag. Willem’s hands dip into the flour, testing to make sure it is not too fine and not too rough. Every now and then, he makes slight adjustments, moving a wooden lever up and down, raise up and lowering the grinding stone slabs.

“Well my mother told me, that I was interested in windmills ever since I was born. But when I was eight years old there was a professional windmiller only one mile away from the house where I lived. So one Saturday I took my bike and went to this miller. And the next 10 years I went there every Saturday. First just helping. When I was 13-years old, they said to me, ‘We’re going to the bakeries. You can grind this. You can sift out that one. We’ll come back in two hours.’”

10 years later, Willem took over the Red Lion Mill. I asked him, why does he mill flour, when he could just buy it in the store? He answers, “Just for fun. I make money with the shop downstairs. Not a lot, but enough. You have do this because you love it.”

The Red Lion Windmill isn’t a museum. It’s Willem’s home and business. It’s his passion. I imagine that the other kids made fun of him when he was a child. He was probably the “weird” boy who sifted flour at the windmill while they all played football. Perhaps that’s why I admire Willem so much.

Later, I stand outside. Watching the Red Lion’s lovely sails swiftly turn, like our short days lives here on planet earth, I think about the courage it takes to follow your passion in life.

OXLAEY

OXLAEY